Hickey: Menace and Mark of Beauty

For as long as the venerable art and practice of putting ink on paper has existed, there has been the scourge of the hickey. This printing blemish has created mountains of spoilage, desecrated works of art and dishonored portraits of the honorable. It has spawned untold towers of ruined paper stacked to the moon and back many times over, stolen weekends and been responsible for a million sleepless nights. It has certainly destroyed careers, and at its most benign, the hickey has caused pressrooms to rumble under torrents of profanity.

And it’s just a dot. But depending on how or where it appears, a very unfortunate and unlucky dot.

A hickey, at least in the context of printing, is a spot or defect in the printed image derived from dust, dried ink particles, separated paper fiber, or other foreign particles that adhere to the blanket, plate, or print matter. It is a bit of crud that gets in between the printed sheet and the print form and is most evident in solids and halftones. Hickies can be especially dangerous in the world of offset lithography, where the significant pressure across the cylinder surfaces, relative speed of the machine, and other stresses (water) to the paper create more favorable conditions for them.

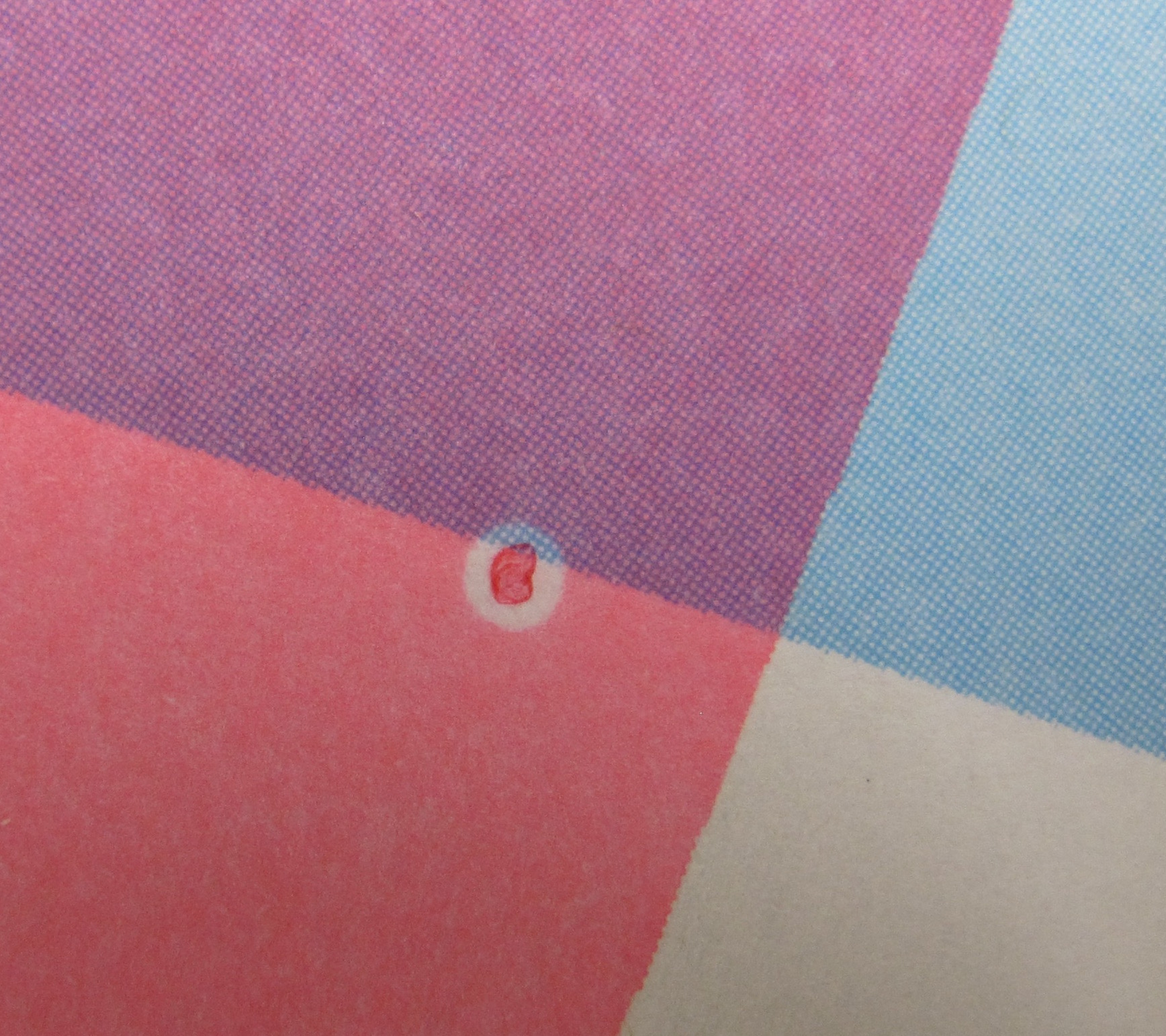

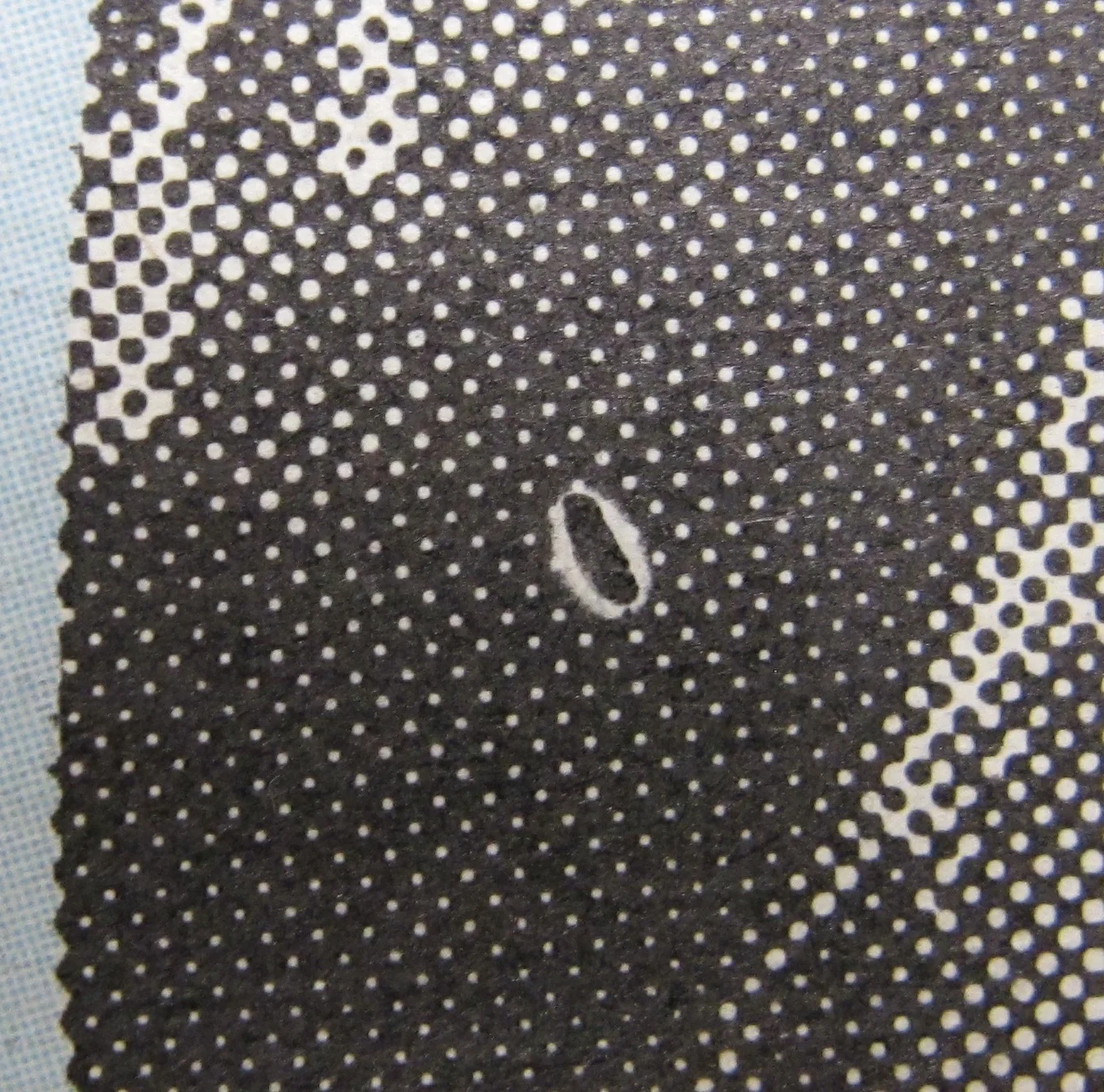

Within the taxonomy of hickies, the classic form is a “donut hickey.” Appearing as a solid dot with a blank ring or halo around it, these ring-shaped hickies, also called fish eyes, bullseyes, the devil’s a-hole, or a million more colorful names thought up by printers through history, are perhaps the most recognizable. Also common are “void hickies,” which appear as blank dots, or specs within a printed area.

Here at our shop we find that of the two most common hickey sources, ink particles and paper particles, paper is to blame 80% of the time. And if that paper stock has been back trimmed with a dull blade or beveled side of the knife, fibers are forcibly dislodged instead of neatly cut, leaving a fuzzy, furry edge. Hickey heaven.

Another culprit: ink tack. If the ink tack is stronger than the cohesive or binding strength of coating or fiber of the stock, pick-outs occur. These might start out as the classic donut hickey, but if the ruptured paper fiber piece becomes saturated with water and less ink receptive, it will print as a void.

It is always interesting to thumb through a lift of printing and do some detective work to find a source of a hickey, and observe how it changed through a run. Often you can find the origin point within the printed sheets. While thumbing through the lift, you may see that the hickey may grow in size, or recede, disappear, or move to another area of the image. There may be one, or many, making up a galaxy of hickies in a single image. Then you’re in trouble.

However, over time and as digital reproduction spills forth in areas formally occupied by traditional print, we’ve felt that the hickey has elevated a bit from its status of pure pressroom menace to that of something of a mark of authenticity. Its spontaneity of occurrence, unique shape and form in every instance of its appearance, and the life arc during a run makes it the wabi sabi of print work.

Don’t get me wrong. We’ll absolutely stop the presses for hickies, keep a keen eye on pull sheets for those characteristic bullseyes, and do our due diligence to avoid them. But now when viewing print ephemera- old show posters, little mag-era independent publishing, and record jackets from the 60s and 70s, the occasional hickey may just enhance the enjoyment of the piece. It reveals the subtext of the print process, communicates a different life separate but parallel to the graphic intent of the artwork. Someone worked hard to bring the printed piece to life, working over whirling machinery and the hiss of ink on rollers. The hickey: scourge, seal of authenticity of real ink on real paper. And depending on where it appears, beauty mark.